This winter, many of us have been captivated by the elegant romances and swirling intrigues of Regency-era England thanks to Bridgerton, the new period drama from Netflix. While we await being able to welcome guests back to some of the inspiring locations featured in the series, you can whet your appetite with some of the marvellous settings that hold real-life stories and secrets which would thrill even the all-seeing Lady Whistledown…

While the lavish gates and stunning wisteria-covered frontage are inventions for the camera, the welcoming sight of the London residence of the Bridgertons can actually be found in the capital itself, and comes with a history befitting a fictional family that captured the attention of royalty.

Ranger’s House, in Greenwich, London, is where the exterior views of the Bridgerton residence were filmed, and boasts a fascinating and lengthy history. Almost one hundred years older than the setting of the series, built in the early 1720s, Ranger’s House was originally built for Captain Francis Hosier, who made his fortune as a sea trader, and who later became a Vice-Admiral. His father was a clerk to the famous Samuel Pepys, but Hosier himself met an unfortunate fate, dying of yellow fever in 1727 during a disastrous blockade of the Spanish port of Porto Bello in modern-day Panama. Ordered to stay offshore and not attempt to take the city (which he could easily have accomplished with the forces he had), Hosier could do nothing but watch as disease took the lives of around 4000 of his soldiers. After Hosier died, disease continued to impact the force, with the deaths of his subsequent two replacements in leadership. The tragic story of Vice-Admiral Hosier moved hearts at home, and the poet Richard Glover wrote Admiral Hosier’s Ghost, the titular spirit of which could not be at rest until the half-hearted approach to military policy learned from the failure of the attack.

The house would not remain empty for long, with the 4th Earl of Chesterfield purchasing the lease in 1748, though he never stayed there very long. Philip Stanhope was an acclaimed wit of his time, and had his maiden speech in Parliament at the tender age of just 20 (and was promptly threatened with a fine for being too young to speak in the House). To pass the time until he turned 21, Stanhope travelled to continental Europe, where he gained intelligence in Paris that thwarted a Jacobite plot. His subsequent years of diplomatic service upon inheriting his father’s title were rewarded with membership to the prestigious royal order of chivalry, the Order of the Garter, the title of Lord Steward. He also developed a friendship with Robert Walpole, our first ‘prime minister’, and, rather ironically, the figure who was given the lion’s share of the blame for Hosier’s failure to decisively capture Porto Bello. After playing a leading role in the downfall of Walpole 1740s, Stanhope went back to Europe, visiting luminaries such as Voltaire and Fontenelle. There’s a portrait of him below.

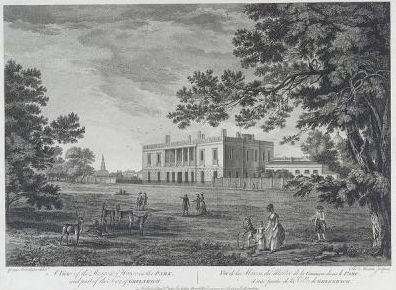

Before long, Stanhope was welcomed back to England to act as the intermediary between the two sides of the new coalition government, William Pitt and the Duke of Newcastle. With an admirable performance as a diplomat in the Netherlands, he was given the position of Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, a position he held for almost two years before taking the position of Secretary of State. In one memorable exchange during his tenure in Dublin, he was woken by false reports of a rebellion in the country. After being told that the people were ‘rising’, he replied: ‘I am not surprised at it, why, it is ten o’clock, I should have been up too, had I not overslept myself!’ He also had a falling out with Samuel Johnson – after Stanhope invested in his project to write the first Dictionary of the English Language, Johnson was insulted by his patron’s lack of interest, writing a sharply worded letter to that effect. Stanhope, instead of being insulted, was delighted by the rhetoric Johnson used in his letter, and would display it proudly to guests. He also described the view from Ranger’s House as one of the finest in the world, a sentiment many echo to this day. You can see a picture of the house from 1791 below.

Some time later, in 1816, the house would acquire its current name and become the official home of the Ranger of Greenwich Park – a royal appointment that carries no official responsibilities. This was shortly after (and fittingly also the period in which Bridgerton takes place), Caroline of Brunswick, who had married and become alienated from the son of King George III and Queen Charlotte, had ended her tumultuous and gossip-ridden residence next door at Montagu House. Ranger’s House thus became the source of fascination through the exact same path that the Queen finds so entrancing in the series – being at the heart of a scandal. If you want a taste of some of the cut-throat intrigues that occurred in real life just next door to the filming location of the Bridgerton residence, you can discover it in our journal entry on park oddities.

Unlike the home of Caroline of Brunswick, which was demolished in 1815, Ranger’s House stands to this day, where in more recent years one has been able to find collections housed inside – first, musical instruments, and then Jacobean portraits. Now managed by English Heritage, the building now houses the Wernher Collection, which features a wonderful selection of paintings. You can see the beautiful facade of the Bridgerton residence for yourself on one of our inspiring Historic Greenwich private tours.

You won’t be able to see the interior of the Bridgerton house with a trip to Greenwich, however – the incredibly impressive interior of the mess hall of RAF Halton, which is known as Halton House, provided the filming location for those grand affairs of the 19th century family, as well as the location for some of the interior shots of the Featherington residence.

Syon House in West London has a truly remarkable history, as well as looking fabulous, so it is only fitting that the interiors were the setting for the Duke of Hastings’ London residence.

The site was originally home to Syon Abbey, a Bridgettine abbey that was among the richest in the kingdom before the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII led to its closure in 1539. Incidentally, almost five centuries later our founder Jack was part of a team of archaeologists that excavated the remains of the Abbey. The land was claimed by the Crown in the immediate period after this upheaval, before the 1st Duke of Somerset leased the location and built a mansion in the style of the Italian Renaissance on the site. That was how it looked when Catherine Howard, the fifth wife of Henry VIII, was imprisoned there for over a year, before being taken to the Tower of London for execution. Henry VIII’s own corpse actually rested at the house for a night during the procession of his jewel-encrusted coffin to its burial place at St George’s Chapel in Windsor.

The home was the scene of some royal drama in 1692, when the future Queen Anne had an argument with her sister, Mary II (who was married to William of Orange, better known as King William III). Mary was infuriated that her sister was friends with Sarah Churchill, Countess of Marlborough, a friendship that would later be depicted in the critically acclaimed 2018 film The Favourite. After Anne was exiled from the court, she took up residence at Syon House, where she gave birth to a stillborn child. Shortly after this, Mary visited her, but instead of healing wounds she demanded Anne end her friendship with the Countess. Anne refused once again, making Mary even more incandescent with rage. You can see how the house looked at this time in the illustration below.

The eye-catching interiors you see on screen in Bridgerton were fitted between 1762 and 1769, when Syon House saw numerous renovations and improvements, including work by legendary landscape architect Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. We have interior designer Robert Adams and his work from this period to thank for the interiors on display in the show – he introduced an eclectic mix of styles, at first look Neoclassical or Romantic, but with traits from the Baroque and even a hint of the Gothic. The rooms sparkle with elaborate details and opulent colour, which makes it a fitting location for Bridgerton to film within.

Today, Syon House welcomes visitors to the stately home which remains the London residence of the Duke of Northumberland, and guests can even stay on the grounds themselves thanks to the construction of the London Hilton Syon Park hotel. With a 200-acre park that sprawls along the Thames just across from Kew Gardens, you will have plenty of space to promenade to your heart’s content!

Wilton House is one of the gems of the Salisbury area, and it features more than you might expect in Bridgerton – it was used for four different homes in the series, including the exterior shots of the Duke of Hastings’ London residence, as well as interior shots of Lady Danbury’s residence, the Palace, and the fictional Clyvedon Castle (the ancestral home of the Dukes of Hastings).

Much like Syon House, the land was occupied by an abbey that had grown incredibly prosperous since its founding in 871 AD and subsequent support from King Alfred the Great, before being torn down and transformed into an ancestral home for those close to the Crown after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. In this case, it was William Herbert, who was made Earl of Pembroke by Henry VIII and who married the sister of Henry’s sixth wife, Catherine Parr, who established his ancestral home on the site in 1542. Perhaps it is fitting, then, that the house would later host the royal court of Queen Charlotte on Bridgerton!

Not much remains of the Tudor house that Herbert built, though the tower that has remained from this era is certainly striking, but this part of the story comes with a fantastic mystery attached. It has long been claimed that none other than celebrated artist and painter of The Ambassadors, Hans Holbein the Younger, was behind the plan for Herbert’s Tudor-era mansion. There is no proof for this, and Holbein died in 1543 (almost a decade before the house was eventually completed), so it would have had to be an unusually speedy design process if that is the case. However, the estate still boasts a ‘Holbein Porch’, which originally served as the grand main entrance to the house before being detached and turned into a garden pavilion in later years, and which show a blending of Gothic and Renaissance styles to such a skilful degree that it doesn’t seem too outlandish to suggest a great master such as Holbein had a hand in its creation. You can see the ‘Holbein Porch’ below.

The next chapter of Wilton House’s story came around 80 years later, when the 4th Earl of Pembroke decided to hire Inigo Jones to reimagine the stately home in 1630. Jones was a master architect, and left his mark across the country with a series of spectacular projects, such as the Queen’s House in Greenwich, Banqueting House (formerly part of the Palace of Whitehall, and later the scene of the execution of King Charles I) in Westminster, and he was the first to introduce Vitruvian rules of symmetry and proportion, as well as the Neoclassical movement in general to the field of architecture in England.

A fire led to the 8th Earl to commission a renovation in 1705, which allowed the Earl to show off the fabulous collection of marbles he had acquired – you can gaze upon some of the famous Arundel Marbles yourself on our private tour of Oxford at the Ashmolean Museum, incidentally, if you don’t feel like a trip to Wilton to get a taste of the collection – but after that the house went largely unchanged for the next century. At the start of the 19th Century, the 11th Earl hired James Wyatt to remove the last vestiges of the Tudor mansion that had remained after Inigo Jones had introduced his Palladian-style vision to the site, and to replace it with features from the Gothic revival movement, such as a new staircase, cloisters, and a new hall that was in the style of ‘Camelot’.

While these adjustments have been roundly criticised by architects since for diminishing the work of Inigo Jones, it gives the site the ability to play the setting for a wide variety of locations, making it a favourite among period drama makers. Eagle-eyed viewers will also be able to see Wilton House appear in the 2005 Keira Knightley / Matthew Macfadyen version of Pride and Prejudice, where it was used for the interior shots of Pemberley, and the ‘Double Cube Room’ at Wilton makes regular appearances on The Crown standing in for one of the formal rooms at Buckingham Palace. In fact, 2020 has been a particularly good year for Wilton House onscreen, as it also played a starring role in the latest adaptation of Emma, where it featured as Donwell Abbey. You can see how the house looks today (including the Tudor tower that remains a part of the building) in the photograph below.

The house and grounds have been open to the public since 1951, and we would be delighted to arrange a visit for you when it is once again possible to do so – it really is a perfect combination with a trip to Salisbury and Stonehenge. Just get in touch to enquire about this possibility, and we will make a perfectly bespoke itinerary just for you.

Perhaps the most spectacular filming location in the series is Castle Howard, just outside York, which was used for the exterior shots of Clyvedon Castle, the country home of the Dukes of Hastings.

The stately home is not a castle in the traditional sense – it takes that name from the ruins of Henderskelfe Castle, which stood on the site when construction commenced on the orders of the 3rd Earl of Carlisle in 1701. The Earl enlisted John Vanbrugh to design the house, who is also known for his creation of the property that would later play host to Winston Churchill just outside Oxford, Blenheim Palace, and Vanbrugh in turn hired Nicholas Hawksmoor, whose work can be seen across London, from parts of Christopher Wren’s St Paul’s Cathedral to the towers of Westminster Abbey. So large and expansive was the Baroque house and its sprawling gardens that work was not completed until over a century later, in 1811.

Castle Howard was devastated by fire in 1940, and though its opening to the public in 1952 helped restore several portions of the house, the entire South East Wing remains a shell, despite the exterior now being repaired. There’s no shortage of space however – Castle Howard is one of the largest stately homes in England, with a grand total of 145 rooms. The fire also hasn’t put off the generations of filmmakers who have come to inspire their audiences with the incredible setting, most notably when it was featured as the titular estate of the 1981 television serial adaptation and the 2008 film remake of the classic novel Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh.

While the house itself is certainly a beautiful one, and the gardens are extensive, here let’s focus on one thing related to the stately home where the interiors of settings such as the Duke of Hastings’ London residence, Lady Danbury’s residence, and Clyvedon Castle were filmed; no, it did not get its name from the popular sport of badminton. In fact, it’s even better than that – the sport was created there, and actually takes its name from the house.

The story goes that the winter of 1863 was particularly harsh, and to stay entertained while they were stuck inside because of the snow the children of the 8th Duke of Beaufort invented the pastime using a lightweight feathered shuttlecock, so that their game wouldn’t damage the paintings lining the Great Hall. While some argue the sport was reintroduced to the country from British India, there is no question that the sport was ultimately popularised at the estate, leading to its name.

Almost a century later, Queen Mary herself caused some discomfort at the house, taking refuge from the bombing of London for much of the Second World War. The Duke and Duchess of Beaufort were less than thrilled about this, remarking when later asked which section of the house Queen Mary had occupied: ‘She lived in all of it.’

Today the house and grounds has been opened to the public, and has been used in several other films, such as 28 Days Later, The Remains of the Day, and Pearl Harbour. The estate also hosts the Badminton Horse Trials, one of only six annual Concours Complet International (CCI) Five-Star events as classified by the International Federation for Equestrian Sports, which places it alongside equestrian events such as the Kentucky Three-Day Event, the FEI World Equestrian Games, and the Olympic Games.

Surely you were not under the illusion that we’d be ignoring Bath’s starring role in Bridgerton? The Holburne Museum in Bath was the city’s first public art gallery when it opened in Sydney Gardens in 1882, and was featured in exterior shots of Lady Danbury’s residence, as well as standing in for some interior ballroom scenes throughout the series. It’s been featured in other period dramas over the years, such as the 2008 film The Duchess starring Kiera Knightley, and the 2004 adaptation of William Thackeray’s novel Vanity Fair, starring Reese Witherspoon.

However, the beautiful Sydney Gardens have been an inspiration for far longer, with Jane Austen herself walking through them on many occasions (she lived around the corner), giving context to her setting of parts of Northanger Abbey in the immediate vicinity. The gardens and the building that would become the museum were the site of many glamorous parties, especially on the birthday of King George III every year, when the gardens were lit with thousands of lamps and fireworks exploded in the sky above – a scene familiar to anyone who has seen Bridgerton! The museum itself houses works from artists such as Gainsborough, Stubbs, Zoffany, and Ramsay, while the ceramics and glass portions of the collection has been enlarged since founding.

Royal Crescent features in some external shots of Bridgerton, and is perhaps one of the most frequently filmed locations on this list. It’s easy to see why – the row of 35 terraced houses with its crescent shaped lawn in the middle is one of the finest examples of Georgian architecture in Britain, and the exterior facades of the houses have barely been altered since construction was completed in 1774. It allegedly takes its name from the residence of Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, who was immortalised in both a grand column memorial in Westminster (that many visitors mistake for Nelson’s Column) as gratitude for his reorganisation of the British Army into a modern fighting force, and in the children’s nursery rhyme, The Grand Old Duke of York, in mockery of his failed military expedition to Flanders.

No.1 Royal Crescent is now open as a museum, and it was this that acted as the front door for the Featherington residence in Bridgerton. It is hard to imagine a trip to Bath that does not include wandering along the gorgeous Palladian residences of Royal Crescent, imagining the members of high society that once flocked here to sample the ’healing waters’ at the popular Roman Baths.

15 January 2021