London has some incredible parks, not least among them the stunning Royal Parks which are rightly beloved across the capital. But some of London’s parks hold secrets just as fascinating as their more grandiose counterparts…

Tucked away in the buildings that surround St Paul’s Cathedral is Postman’s Park, which, despite its small size (just over half an acre) is actually one of the largest open spaces in the crowded ancient delineation within the metropolis that is the City of London. Beneath the pleasant flower beds and grass lies a grisly story – the park is elevated above street level due to the amount of corpses squeezed into the space, as it served as a churchyard until 1880.

But the real star of this park is the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice. The brainchild of painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts, it was originally proposed in 1887 to coincide with the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, but was refused. The project was intended to commemorate ordinary people who had lost their lives saving others, and who would otherwise risk being forgotten. In 1898 the vicar of St Botolph’s Aldersgate church approached Watts, and it was he who suggested Watts build his memorial in the new park next door that had previously been the churchyard. The vicar, of course, had his reasons – his church desperately needed money to stay open, and he hoped that this memorial being placed in the park next door would elevate its profile.

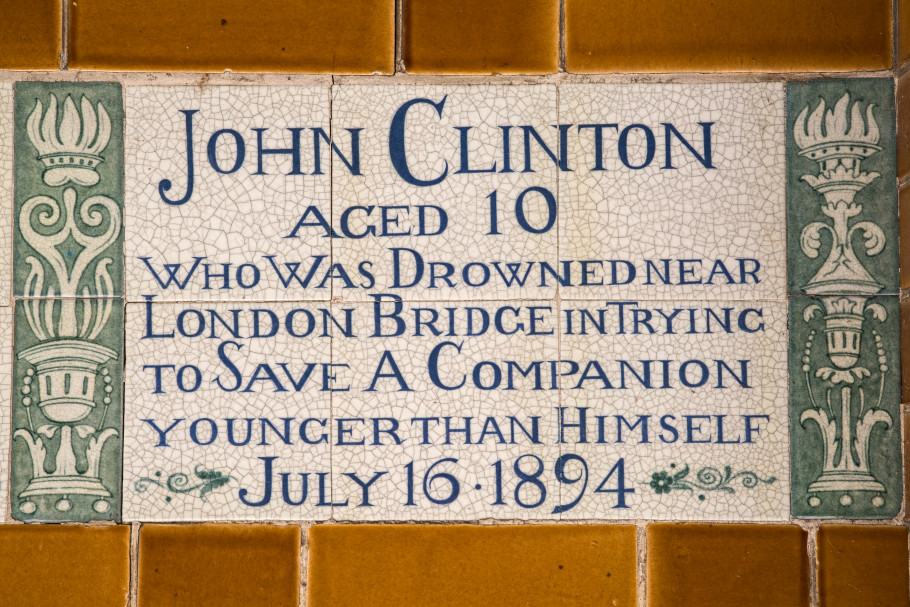

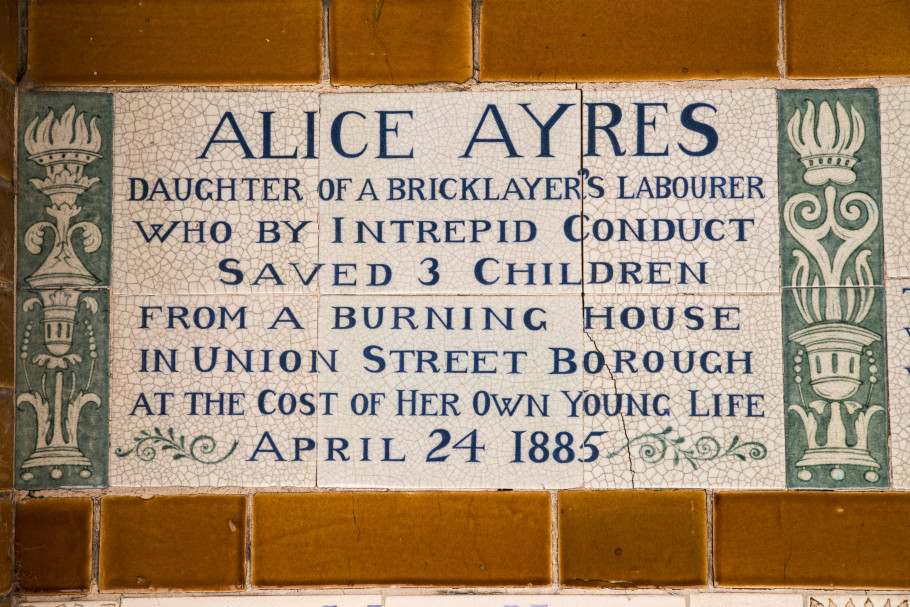

The memorial takes the form of a covered wall with tablets along it. Originally there was to be 120 ceramic tablets, each memorialising a different heroic figure, but by the time work ceased on the project altogether in 1931, only 53 tablets were in place. In 2009, the first new tablet in almost 80 years was added, memorialising the sacrifice of Leigh Pitt, who saved a boy from drowning in the canal at Thamesmead but tragically drowned himself in the process.

Fans of Jude Law, Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts, or Clive Owen may remember the park from the 2004 film Closer, in which it forms a central plot point. You’ll be able to see the tablet dedicated to the memory of Alice Ayres, who saved three children from a fire in 1885, but perished in the blaze in the process. Whichever of the many stories of self-sacrifice and heroism you come away with, the fact that these remarkable people were just everyday Londoners is one thing that unites them and inspires us.

You may already be aware of the story behind Crystal Palace Park’s name, which has its roots in the stunning glass structure constructed to house the Great Exhibition in 1851. But less well known are the creatures from before time that roam this green space in south London!

That’s right, forget Jurassic Park, you can get your fill of dinosaurs right here in Crystal Palace Park. When the Crystal Palace itself was moved to the large green space in South London after the Great Exhibition, it was decided that ornamental gardens should be created around it in order to give the structure a luxurious setting befitting its status. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was commissioned to capture the public interest in the new discoveries of fossilised beasts from a primordial time, and set about creating the first ever live-sized models of extinct animals.

By 1853, the first models were in place on three artificial islands, each covering a different time period – the Paleozoic (541-252 million years ago), the Mesozoic (252-66 million years ago), and the Cenozoic (66 million years ago to the present day). The animals were first built full-size in clay, from which a mould was taken allowing cement sections to be cast, all in a workshop Waterhouse had set up at the site itself. The larger sculptures were hollow with a brickwork interior. Hawkins celebrated the opening with a grand banquet on New Year’s Eve inside one of the Iguanodon sculptures, and public interest was so great that replica miniature sets of the animals became a popular souvenir.

Unfortunately the rapid growth and popularity of the emerging science of palaeontology was also part of the undoing of Hawkins’ great project. Within years, new details of the creatures Hawkins had sculpted were discovered, and quickly showed the early understanding portrayed in the models to be deeply inaccurate. The authorities, balking at the massive cost of each sculpture, cut funding to the project, leaving several unfinished or discarded, and by the time the Crystal Palace itself burned to the ground in 1936, the extinct creatures were almost entirely hidden by dense foliage. In the 1950s, the models were redistributed throughout the park, which exposed them to even more wear and tear.

With a newfound focus on Britain’s past with the onset of a new millennium, the park and its dinosaurs were fully restored in 2002, and received an enhanced heritage protection status in 2007. The models are now protected by a dedicated group of fundraisers, the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, who led a high profile project (with support from Guns ‘n’ Roses guitarist Slash) in 2018 to build a new bridge to the islands. Now you can walk among the sculptures for yourself, and relive how the Victorians must have felt seeing these awe-inspiring creatures in life-size for the first time in the beautiful setting of Crystal Palace Park.

It may seem a little unusual at first, a statue dedicated to a Disney protagonist a stone’s throw away from Kensington Palace (the home of Prince William and his family). But the story behind this statue goes well beyond the 1953 cartoon adaptation of the children’s classic.

J.M. Barrie first wrote about Peter Pan in 1902, in which fairies and birds teach the young Peter to fly in the idyllic surroundings of Kensington Gardens. In 1904, Barrie reintroduced Peter in play form as ‘The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up’, before the shape of the story as we know and love it was finally formed in 1911 in Barrie’s book ‘Peter Pan and Wendy’. Peter’s relationship to the natural world was always key to his character – even his surname, Pan, comes from the Greek deity who represents the untamed wilds. This contrast to the strict Edwardian social mores that were drilled into the upstanding metropolitan inhabitants of early 20th Century London made the book “ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children but really a play for grown-up people”, as George Bernard Shaw put it. The vivid connection to the beautiful Kensington Gardens in the literature allowed people to imagine that they too were escaping to Neverland and recapturing their childhood.

In 1912, the Peter Pan statue appeared in Kensington Gardens, seemingly out of nowhere, on the very spot that Barrie had described in his original Peter Pan story. The commission had been planned for over a year, of course, but Barrie was very clear in his desire to erect the statue with no fanfare or announcement – he wanted children visiting the park to stumble across the new statue, as if it too had appeared magically with the help of the fairies. This, of course, necessitated placing the sculpture without gaining the proper permission from the authorities, something that was immediately forgiven, and which seems rather apt considering Peter’s mischievous nature! Perhaps Barrie was simply making up for something that he ultimately felt was lacking in the statue – he complained that the work didn’t show the Devil in Peter’.

As magical as the appearance of the Peter Pan statue was, the potential stories behind Barrie’s inspiration for the character make it bittersweet. One proposal is that he is modelled after Barrie’s own older brother, David, who died in an ice-skating accident the day before his 14th birthday. His mother and brother thought of him as forever a boy. Or perhaps he was modelled on the Llewellyn-Davies brothers, who Barrie informally adopted after their parents died tragically, and who share the names of several other characters in Peter Pan’s world. Whatever the case, Barrie performed one final good deed when he gave Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital the rights to Peter Pan, allowing children in need to benefit over a century later from the story of the child alive in all of us.

You can explore every nook and cranny of Kensington Gardens, as well as Kensington Palace and the area’s fantastic collection of museums, on our Kensington Palace & Museum tour.

You might head west in London for a lot of reasons – perhaps you’re taking a trip to the Design Museum, or maybe you’re heading up to Notting Hill and its delightful mews houses. Whatever the cause of your visit, you’d be a fool not to take a wander in the beautiful Holland Park, and check out the serene hidden Kyoto Gardens it contains.

The gardens were built in 1992 to celebrate the longstanding friendship between Japan and England on the occasion of the Japan Festival held that year, and has several features which make it a perfect place to while away the hours, including the central pond and tiered waterfall – with the sound of water flowing away, you’ll feel the stress of the city melt away. The plants that fill this scenic space are all native to Japan, while the ishi-dōrō (stone lanterns) around the pond add to the ambience of this special garden. It is particularly worth visiting in autumn, when the leaves on the trees turn to a gorgeous orange and red hue, or to see the delicate pink blossoms on the sakura trees in spring.

It’s also entirely free to enter, so it’s a fantastic opportunity to see a very different green space in London. But do be aware that you’ll have to share the space with some unusual inhabitants – a flock of peacocks call the gardens home, and love to lazily hunt for insects in the shady corners of this zen garden, while a group of koi carp swim around the water feature at its centre. You might also spot an authentic Japanese tsukubai, or wash basin, traditionally placed at the entrance to holy sites for ritual hand cleansing (often prior to a tea ceremony).

It’s not the only Oriental influence in this park – you can also visit the Fukushima Memorial Garden, opened in 2012 to commemorate the disastrous 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear incident in Japan.

With the Royal Observatory, Royal Maritime Academy, and stunning green spaces, not to mention gems like the Cutty Sark, Greenwich is a fascinating part of London. But nestled in the park is something absolutely remarkable – the last remnants of a royal residence, the site of debauchery and tragedy.

The story begins with Princess Caroline of Brunswick’s wedding in 1795 to Prince George, who would later become King George IV. Unfortunately the wedding was more down to the wealth of Caroline than any significant attraction, and George found Caroline so unattractive that he asked for brandy – while Caroline remarked that George was ‘very fat, and nothing like so handsome as his portrait’.

By 1801, George deemed that Caroline had served her purpose – Parliament had increased his allowance due to Caroline’s eligibility, and his debts were somewhat eased, so the couple separated, with Caroline moving into Montagu House near Blackheath. The residence was the site of many liaisons with the great and powerful, but Caroline had a major falling out with her new neighbours, Sir John and Lady Douglas, who then accused Caroline of infidelity. Four of the most powerful men in the country, the Prime Minister, the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice, and the Home Secretary, assembled to form a secret commission named ‘the Delicate Inquiry’ to investigate the claims.

Though the commission found no foundation for the allegations, gossip spread, and the increasing isolation took a severe toll on Caroline – her husband, now Prince Regent after the permanent insanity of his father King George III, increasingly prevented her from seeing their daughter, and leaked the allegations from the Delicate Inquiry. Jane Austen, writing at the time, expressed sympathy, saying: “Poor woman, I shall support her as long as I can, because she is a Woman and because I hate her Husband.”

In 1814, Caroline finally gave up, after being excluded from any celebrations marking the defeat of Napoleon. She negotiated an agreement with the Foreign Secretary – an allowance of £35,000 a year in exchange for leaving the country. Caroline truly lived her best life in exile, travelling around Europe before taking up residence in Villa d’Este on the shores of Lake Como. But her debts were increasing, and, in 1817, tragedy struck – her daughter, Princess Charlotte, had died in childbirth. Prince George refused to even write to Caroline to inform her of the death of their child, leaving Caroline to find out third hand from a letter sent to the Pope informing him of the news. The tragedy left Caroline heartbroken, but also removed the possibility of the restoration of her status through the ascension of her daughter to the throne.

George, meanwhile, had not given up on his goal to rid himself of his wife, and set up another commission to find evidence that would enable him to divorce her in 1820. That year, his father finally died, and Caroline returned to Britain to assert her position as queen in preparation for an 1821 coronation of George. Like her daughter had been before her untimely death, Caroline was hugely popular with the British public. This proved to be the undoing of George’s final effort to divorce Caroline, the introduction of a bill in Parliament that would legally declare Caroline to have committed adultery and allow him to end the marriage he had so long felt imprisoned in. But the bill was so deeply unpopular, and provoked such outrage, that the government had no choice but to withdraw the bill.

Caroline was barred from attending the coronation of the new King George IV, but turned up at Westminster Abbey anyway, where she was turned away and had the doors slammed in her face on the orders of her husband. That night, she fell ill, and she died three weeks later. Her funeral procession was routed away from London to avoid unrest – this had the opposite effect, with crowds forming to force the bier through the capital instead of its intended route.

Montagu House was torn down on the orders of George in 1815, after Caroline’s exile, and now a set of tennis courts stands where the mansion once did. But among the surviving walls is a terrace with a plunge pool cut into it – all that remains of the sordid scandals and political manoeuvring that dominated Queen Caroline’s life here, and a reminder of the alleged parties and debauchery that fuelled a royal vendetta.

You can explore Greenwich Park, where Queen Caroline’s Montagu House once stood (and even see the infamous bathtub!) on our Historic Greenwich tour, which offers even more fantastic stories and characters.

10 December 2020